My final semester of university was by far the best. I had found a place I could belong at the Arizona Daily Wildcat. I could do the job, I had friends with similar interests, and the days were full of interesting challenges.

I graduated in December 1991 and enjoyed the holiday break with my family and my friends. I ran into another journalism student on New Year’s Day 1992 who had just landed a job as a reporter at a small-town newspaper. And I was jealous. I had more experience, a better resume, etc. So I applied myself to finding a job rather seriously. In retrospect, the amazing part is I succeeded rather quickly.

Within a month of graduating, I had landed a job at the Arizona Daily Sun in Flagstaff as the special sections and entertainment editor. The pay wasn’t great, but it was a step in the door and an exciting opportunity. Most of the staff at the Sun were working their first or maybe second job out of college, so in some ways it was almost a continuation of the Daily Wildcat. I moved into a house with some of my co-workers — we’re still friends to this day — and I started work.

Comics had not been my top priority during these months. I still had picked up the Claremont-less X-Men, but not much else. It took me until maybe March of 1992 before I was settled enough to get back into comics.

As with many of us, Wizard was at fault. I was at Bookman’s in Flagstaff and spotted a copy of Wizard #7 on the racks, bought it, and enjoyed it. Boy, did I hate the editing. Typos galore in those early issues. It took a long time for Wizard to get up to speed in this department. What it did have was attitude. And for all the faults of its monthly price guide and hyping of hot books, it did have its finger on the pulse of what was going on. And there was a lot going on.

Image Comics was founded in February 1992. I ordered a couple copies of Youngblood #1 by mail because there was no comic shop at that time in Flagstaff, aside from Bookman’s, which had a spotty selection of new comics. It was late, so it took a few more months than expected to show up, and when it did it was underwhelming from a story perspective.

There’s no doubt Rob Liefeld’s art had energy. His characters had an edge to them that the established superheroes of Marvel and DC lacked. Youngblood reflected the bro culture of the early 1990s. These heroes had money, and good looks, and girls. Young men liked that. This was something they could aspire to more easily than ridding the world of crime, fighting for truth or justice, or eradicating prejudice.

But lacking a larger message or purpose meant Youngblood and its many imitators were disposable. The art was cool, but there was too little behind it to hold your attention. Plus, Image books were insanely late. More on that soon.

Marvel and DC made Image Comics possible. Marvel shoulders a bit more of the blame because it was all about the money under the ownership of Ronald Perelman. The change from the free-for-all of the 1970s and the professional passion of the early 1980s gave way to greed. Whoever could make Marvel the most money was in, and everyone else was out. And even if you were in, nobody was going to listen to you or treat you as anything but expendable. It must have been miserable for the folks who were there in the heyday of the 1980s when creator pay and freedom were relatively high in comics.

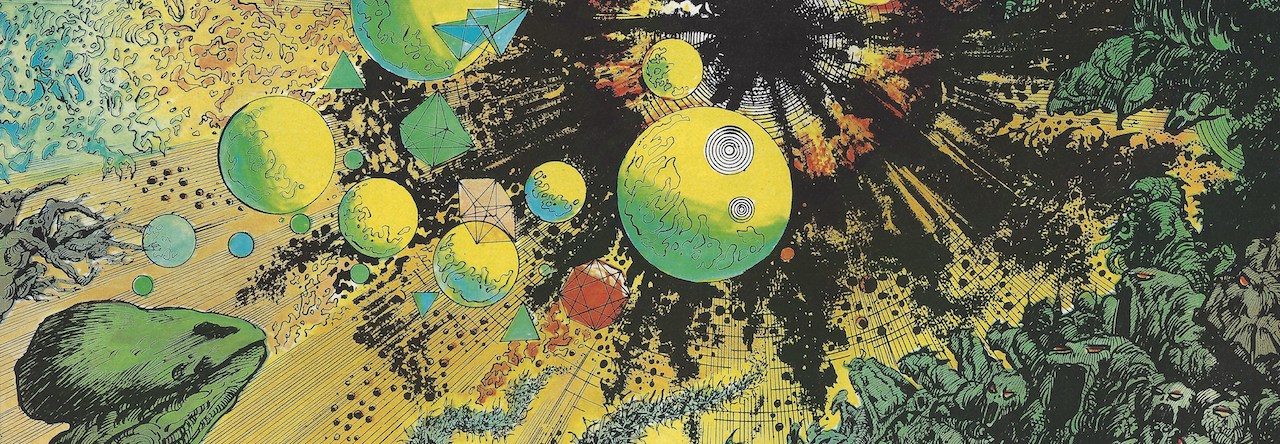

Make no mistake, Image was the biggest thing to happen to comics since the direct market. Despite not being a good read, Youngblood #1 sold more than million copies. It was followed by Spawn, which got out two issues before the second issue of Youngblood. Savage Dragon was next, followed by Shadowhawk and Brigade, which would have two issues out before Youngblood #3, WildCATs and CyberForce.

The visual energy Liefeld, Todd McFarlane, Erik Larson, Jim Valentino, Jim Lee and Marc Silvestri brought to these books is undeniably exciting. Fans eagerly awaited the next issue and, thanks in large part to Wizard’s breathless coverage of these books and their collectible value, speculators did as well. The crossover between readers or fans and speculators was quite high. Many fans routinely bought multiple copies of any new Image Comic – one to read, the rest to save. The true speculators, who bought entire cases of a new Image book to hold and flip once it had sold out, were more rare but definitely there.

Creatively, the first issues of these books were great to look at and their shortcomings on the writing side were forgivable. These artists were new to writing, and many comic book series took some time to find their creative footing. The frustrations only arose once the wait for the books was not rewarded by improvements.

Even more frustrating as a fan was watching the Image artists behave like superstars while their fans waited for the next issue. They appeared at conventions, did store signings, sat for interviews with the comics industry press and mainstream media, and announced exciting new projects. But those books took months to arrive, and disappointed when they did. And in these interviews the artists rarely addressed the elephant in the room: Where were the books? Making comics is a time-consuming activity, and it’s even more so when you’re not divvying up the labor. One person plotting, penciling, scripting and inking a comic takes a lot longer than having one person on each of those jobs. It’s quicker when the penciler receives a script, draws the issue to hand off and then can start penciling the next one. That’s how books can meet a monthly schedule. The exceptions, such as Dave Sim on Cerebus, do so because of the personal dedication. Sim did interviews and conventions, but his primary job was to stay home and create Cerebus, which he did despite the apparent impact it had on his mental health.

The fervor for Image was intense. Anywhere I saw them for sale, I was tempted to buy them. I picked up a number of Image titles at Amazing XX in Flagstaff, others at AAA Best, and even others at shops around Phoenix such as All About Books & Comics and Atomic Comics. I even remember seeing copies of Shadowhawk #1 without the embossed foil cover on the newsstand at a 7-11 in Flagstaff.

What was going on at Marvel and DC? Well, artists and writers came and went. Folks like Roger Stern, Louise Simonson and Jon Bogdanove went to DC, while other talents like Steve Englehart, Bob Layton and Steve Ditko landed at Valiant. Jim Starlin returned to Marvel to write Silver Surfer, while Byrne was back on She-Hulk. Peter David was reliable on Hulk, while Batman continued to ride the wave of popularity that started with the 1989 movie and was heading for the sequel and an animated series.

And this is where Valiant comes in. Early Wizards were all about Image, but they also were into Valiant. Rumor has it that powers at Wizard were heavily invested in Valiant comics and promoted them so they could make money. But that really didn’t matter because Valiant filled a very different niche in the market. That niche was delivering entertaining, interesting stories that shipped on time – what everyone wanted from Image Comics, minus only the splashy artwork.

By spring of 1992, a small comic shop had opened in Flagstaff. It was in a hollowed out building on Beaver Street and lacked racks for new comics, some of which were stacked on the floor. My first Valiants were Magnus Robot Fighter #12, Solar #8 and Harbinger #5 and 6.

My search for back issues led me back to Phoenix, where I landed at Ken Strack’s AAA Best Comics. Still located on Seventh Street, Ken was happy to set me up with a pull list that included discounts on all pre-orders, and I was back in the game. I was visiting Phoenix about once a month, so I was picking up a rather large pile of books that I would work my way through and finished by the time my next trip came around.

Everyone talks about 1986 as the most pivotal year in comic books. But 1992 has to be a close second. Not only were Image and Valiant exploding on the scene, but comics in general were booming. Dark Horse had been around for a while, but achieved a new level of mainstream success with projects like John Byrne’s Next Men, Frank Miller’s Sin City and Grendel: War Child. Malibu got a huge influx of cash as the early service publisher for Image. DC’s proto-Vertigo line was building prestige with The Sandman, Hellblazer and Swamp Thing. Understanding Comics was published. Maus won a Pulitzer. Indie and self-published titles such as Cerebus, Bone and Strangers in Paradise were making waves and people were paying attention.

For the first time that I remember, conventions started to crop up in Arizona. One was held at a hotel in downtown Phoenix that featured as guest Dave Sim of Cerebus, James Owen of Starchild, and Martin Wagner of Hepcats. I bought and read the first volume of Cerebus, which I have signed with a sketch from Sim, and the first issues of Starchild, also signed. I wasn’t interested in Hepcats for some reason. I also was able to fill in my Valiant collection right around the time Unity began.

Valiant was a bit of a revelation. They honestly didn’t look like much, but once you cracked open the books and read them, they grabbed you. Especially in the early days, Valiant had the advantage of story. Each issue told a complete tale, even when it was continuing. The Valiant Universe was grounded in reality in a way that Marvel and DC had not, and it made for compelling reading. It also was still small enough that you could collect the back issues and get the entire story, which was important as Unity approached.

Unity was heavily promoted in the summer of 1992. It was a crossover, sure, but it also was offering a free zero issue with a cover from Barry Windsor-Smith. I was unfamiliar with the Gold Key characters Valiant was using, but fans who were spoke well of the updated versions of Magnus Robot Fighter and Solar: Man of the Atom. Valiant also made waves in the collecting side of things, first with the coupon-clipping giveaway campaigns for zero issues of Magnus and Harbinger, as well as the gold editions of books like Archer & Armstrong. The covers for the first month of Unity books were by Frank Miller, with the second month’s covers by Walter Simonson. And Valiant had a true breakout star artist in David Lapham, who progressed from novice to pro in the span of a few issues of Harbinger.

Repeating the drama of the previous summer, when Claremont left X-Men, news spread that Shooter was out at Valiant. I remember checking the Valiant books that shipped after this news broke, and it took a couple months for the company to address it. What exactly happened was difficult to know at the time, but Shooter made it clear later on in convincing accounts that it was the greed of his former partners that lead to his ouster. As a fan, seeing that Winds0r-Smith was sticking around in some kind of official capacity was encouraging, but the excitement quickly faded and soon he was gone. Valiant was a shell of its former self and I soon dropped their books – there was an avalanche of new material being advertised for 1993 and dollars would need to be spent judiciously.

Before that, however, came my first work-life crossover with comics. All it took was for the Man of Steel himself to bite the bullet.

Leave a Reply