So let’s go through the theatrical cut of Star Trek: The Motion Picture:

Right from the start, everything is much more serious than it was in the original series. In case you don’t know why there’s a long blank screen while “Ilia’s Theme:” plays, it’s because this was one of the final movies Hollywood released with an overture. These were common on prestigious pictures especially in the 1950s and ’60s, though the practice had largely faded out by the early 1980s. I remember the 1980s well, and the previews — once accurately known as trailers for appearing after the credits of a feature — ran before the movie. These days, there’s about 20 minutes of rules and previews before most movies, so I doubt anyone would have the patience for an overture.

The credits also are serious, appearing as white text on a black background as the theme music plays — over and done with, lickety split. This movie has two possessive credits: A Gene Roddenberry Production and A Robert Wise Film. I’m not a fan of possessive credits because they suggest that one person (or in this case, two) made the film, which is (almost) never true. But it does reflect the behind-the-scenes jockeying for position detailed in the previous post.

Of all the parallels with Star Wars, the opening is the most obvious as the camera imitates the massive Star Destroyer zooming overhead with a loving pans and pivot around a trio of powerful Klingon warships on their way to intercept V’ger.

The Klingon design here is much more extreme than we’d seen in the original series, or would see later in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock and Star Trek: The Next Generation. The ridges on the Klingons’ skulls are huge and they have fangs.

Mark Lenard, who played a Romulan commander in the original series and Spock’s father, Sarek, in the original series, features and TNG, is unrecognizable as the Klingon commander. It is nice, though, that they gave the role to a fan-favorite instead of an unknown actor.

And the Klingon theme and development of a gutteral Klingon language all have stood the test of time.

The new Klingons are nothing to V’ger, who at this point is so amorphous a presence that it’s not easy to always know exactly what’s going on here. As with most sequences in this movie, the opening is overly long. There’s lots of procedural shots showing how the Klingons order the firing of photon torpedoes, etc. And the Starfleet response on the Epsilon 9 station is a scene that similarly takes an indirect route to achieving its purpose in the story, which is revealing the threatening object is headed for Earth.

What’s disappointing is the Klingons appear here and are done with. I think some good action elements could have been brought into the movie if the Klingons returned later in the movie to conflict or cooperate with Starfleet in solving the V’ger mystery.

Mark Lenard, left, as the Klingon commander in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

Mark Lenard, left, as the Klingon commander in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

The visual effects here are elaborate but definitely shaky. Adopting the techniques ILM used to great effect in Star Wars, the models are detailed and the motion is smooth and to scale.

The compositing is the tricky bit and it shows the limitations of the era’s techniques. There’s lots of lighting mismatches and an obvious patchwork look to many of the effects. All of this was very hard to do, by the way, working with film and pre-digital optical printers. Even ILM struggled to get it right, as you can see from the transparent matte effects in the original version of The Empire Strikes Back.

David Gautreaux as Epsilon 9’s Commander Branch.

David Gautreaux as Epsilon 9’s Commander Branch.

Epsilon 9 offers a first look at the new Starfleet, which is sleek and posh and unimaginably dull at the same time. The new uniforms can’t help but look like pajamas, with their muted pastel tones and leisurely cuts. I’ve read Gene Roddenberry always thought we’d evolve to unisex clothing and that the sexy bodies underneath the clothes would shine through no matter what. Obviously, not an accurate prediction — ever, I’d say — but it does save on costume designs, if not fitting and fabrication.

Behind-the-scenes photo of Leonard Nimoy as Spock on the Vulcan set.

Behind-the-scenes photo of Leonard Nimoy as Spock on the Vulcan set.

Next, we cut to Vulcan, which looks terrible. Our first image is a glimpse of Spock as a Vulcan monk with long, ragged hair looking up at the hot sun amid. It’s supposed to look like a rocky plain with steam from lava rising up, but it comes across like Spock’s looking for dropped quarters and empty bottles in the parking lot of a cheap Hollywood liquor store. The matte painting is awful. The supposed giant statue looks like the work of a small child and the moving planets are scientifically inaccurate and just plain dumb.

Shot of Vulcan that’s mostly a matte painting.

Shot of Vulcan that’s mostly a matte painting.

To be fair, this was not how this sequence was meant to look and this was one of the big casualties of the visual effects production difficulties. But to spend that much money on this movie and this is the result is … unfortunate, as Spock would say.

Storywise, we find out Spock’s been trying to achieve pure logic, a state the Vulcans call Kolinahr. He’s about to graduate, when the siren call of V’ger spoils it and the priestess declares he’s failed. Further mucking up this scene is the dubbing of Vulcan language over actors who are obviously speaking their lines in English. The lip synch is bad and the trick obvious, cheesy and, well, unfortunate.

Kirk’s shuttle zips past the Golden Gate Bridge to Starfleet Headquarters.

Kirk’s shuttle zips past the Golden Gate Bridge to Starfleet Headquarters.

We then cut to Starfleet Headquarters in San Francisco. I think this is the first official reveal of its location, as Kirk travels past the Golden Gate Bridge in an air shuttle on his way to reclaim command of the Enterprise. Again, the matte painting of the interior is weak and obvious. You can see the borders of the matte painting and the figures in the distance are not moving.

Shatner looks good as Kirk — he’s in shape, had his hair done (or at least Shatner could afford a new toupée), has a spiffy white admiral’s uniform, and brings some energy to a short exchange with a hapless Vulcan named Sonak.

Interior of Starfleet Headquarters. Most of this is an unfortunately very-obvious matte painting.

Interior of Starfleet Headquarters. Most of this is an unfortunately very-obvious matte painting.

By the time we get to the next bit of dialog, the movie’s pacing problems are already becoming clear as the next setting, an orbiting Starfleet station, is over-established with multiple long, slow shots of its operations and more of Goldsmith’s lush score to tell us how majestic it all is.

Kirk beams up to an orbiting office platform where Scotty tells him the transporters aren’t working, so he has to drive Kirk over to the drydock where the Enterprise is preparing to launch. Slowing down the movie even more is some clunky exposition explaining the unlikely circumstance of the Enterprise being the only ship Starfleet has around its home planet to send out to intercept this mysterious object that’s threatening its home world.

The refitted USS Enterprise is revealed in drydock.

The refitted USS Enterprise is revealed in drydock.

The reveal of the Enterprise is a sequence I happen to adore, despite going on and on and on some more, while advancing the story exactly not at all. Most of it has to do with Jerry Goldsmith’s rousing musical score, which gives all the loving shots of the upgraded, ready-for-action, all-new Enterprise its 2001-inspired gravitas. The cuts back to Kirk and Scotty “watching” all this as a grip moves what looks like a garden lattice in front of the lighting is pretty bad, as are the optical effects placing them in the pod. But the shots of the Enterprise are gorgeous, lush and detailed. This is the USS Enterprise that the fans always wanted to see, and even though everyone deep down knows this sequence is masturbatory, it’s still quite, ahem, satisfying.

Now, things start to pick up a bit. Kirk returns to the bridge and is welcomed back by Uhura, Sulu and Chekov, who are still right where we last saw them. I do like that some of the new crew are loyal to Decker and wary of Kirk. Had this become a series, that would have been an interesting conflict to resolve.

There’s a couple odd things I always notice in this scene, which is much longer in the extended edition: One is the practical effect that looks like they hung a pair of legs from the ceiling with a disc attached to the feet to make it look like they were using some kind of levitation technology to change the lightbulbs.

The second is the blurring effect from Wise’s use of a split-diopter lens. That’s a lens that splits the frame into more than one depth of field — in this case, a character like Kirk is in focus in the foreground and the background immediately behind him is blurry, while the other half of the frame has a character further back on the bridge in focus. I find it distracting and puzzling since it’s so obvious.

A split diopter lens was used in this shot to create different depths of field.

A split diopter lens was used in this shot to create different depths of field.

Now we get at our first look at one of the longest-running sets in Trek history: the engine room. This was revamped and reused all throughout The Next Generation and well into other series and Next Gen sequels, complete with the silly little elevator between levels.

And we meet Captain Willard Decker. It’s not overtly mentioned in the movie, but I always thought Decker was the son of Commodore Decker, who went mad and rammed the USS Constellation down the throat of the alien menace in the original series episode “The Doomsday Machine.” Playing Decker is Stephen Collins, who was a rising actor at the time who’d appeared in numerous TV guest starring roles. After Trek, he starred in a series called Tales of the Gold Monkey, which was a short-lived attempt to cash in on the success of Raiders of the Lost Ark, was married to “V” star Faye Grant, and then starred as a preacher in the long-running series 7th Heaven opposite Catherine Hicks of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home fame, before accusations of sexual impropriety with underage girls effectively ended his acting career (and marriage). But that’s neither here nor there at this point.

Stephen Collins as Commander Willard Decker.

Stephen Collins as Commander Willard Decker.

Decker personifies Kirk’s fears that he’s too old, too out of date, too washed up to live up to his glory days as a Starfleet captain. (I’m sure this reflects Roddenberry’s own insecurities after being unable to replicate the success of Star Trek.)

It stands in sharp contrast with the admiration Will Riker shows Captain Picard in Star Trek: The Next Generation. I think Riker is a much more likeable character than Decker would have turned out to be, but we’ll never really know.

A pair of Starfleet officer die a horrible death without having to watch the rest of “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

A pair of Starfleet officer die a horrible death without having to watch the rest of “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

The transporter accident is easily one of the most messed up and scary sequences in any version of Star Trek. I don’t know what made that screeching noise, but it’s damn creepy with the images of the figures distorting in the transporter beam. Kirk’s not too convincing in telling Janice Rand that it’s not her fault. And I really kind of want to know what the pile of flesh that returned to Starfleet headquarters looks like.

Another interesting note on this scene comes from the novelization of the movie, written by Roddenberry (much more on that later), in which he reveals Kirk’s romantic relationship with Vice Admiral Lori Ciani, who was the other person killed in the transporter accident.

Fans populate the extras in this recap scene from “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

Fans populate the extras in this recap scene from “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

At this point, we’re a half hour into the movie, so what’s a better idea than a plot recap on a huge, expensive and mostly unnecessary set? That’s exactly what we get as Kirk assembles the crew on the two-level recreation deck. The crowd here is full of fans who had helped keep alive interest in Star Trek over the previous decade. Among them: uber-fan and author Bjo Trimble and “The Trouble With Tribbles” scripter David Gerrold. It’s a straightforward update, then advances things a bit with Uhura taking a call from Epsilon 9 in which we learn the object is 82 AUs in diameter. AU stands for Astronomical Unit and is the distance from the Sun to the Earth, about 93 million miles. So 82 AUs is about 7.6 billion miles, making it at least as large as our solar system as measured by the orbits of Neptune and Pluto. There also is a nice, slightly scary moment in this scene in which a spacewalking astronaut is floating toward the camera as Epsilon 9 is digitized in the background. The figure moves abruptly as the shockwave hits, in a way reminiscent of how Stanley Kubrick moved his spacewalkers in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Stephen Collins as Cmdr. Willard Decker welcomes Persis Khambatta as Lt. Ilia aboard the bridge of the USS Enterprise in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

Stephen Collins as Cmdr. Willard Decker welcomes Persis Khambatta as Lt. Ilia aboard the bridge of the USS Enterprise in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

But before the Enterprise can launch, we still have a few more characters to introduce. First, there’s Lt. Ilia, played by the beautiful and exotic but (appropriately) stiff Persis Khambatta. I thought (and still do) that her shaved head is a great look. I think it would have been really fun to see that character on a weekly series, but it was not to be.

Roddenberry had put a lot of thought (probably too much) into the super sexed up Deltans, almost none of which makes it to the screen. I wonder if every TV show on Delta would be classified by humans as pornography? They were supposed to exude super pheromones that made all the human men around her crazy excited. I think it’s funny that the most obvious portrayal of this on screen comes from Sulu, as George Takei was not yet out as a gay man when the movie was made. Khambatta looks exotic but her performance is very reserved and almost robotic, so the sensuality she was supposed to exude doesn’t play at all in the movie. Her declared oath of celibacy comes across more like she’s some kind of a nun in a convent. Again, if this had gone to series, I’m sure the character and her impact on the men around her would have been more fully explored.

DeForest Kelley as Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy accepts Captain Kirk’s request for his help in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

DeForest Kelley as Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy accepts Captain Kirk’s request for his help in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

And, finally, McCoy comes along to give the whole shebang a few lively moments and remind everyone why they liked this stuff in the first place. First, he looks like he’s been having a great time with that beard, weird medallion and leisure suit. And, as always, McCoy gets the best lines, ranting against Kirk for being “reactivated” to Starfleet duty. DeForest Kelley was, by all accounts, a very gentle and kind man, but as a performer he was at his best when he was griping and complaining as he does here, with gems like: “And they probably redesigned the whole sick bay, too! I know engineers, they love to change things!”

With everyone introduced, the movie now — finally! — has to get going with its plot. We’re 35 minutes into the movie, by the way. And we get more fanfare and procedural jargon as Kirk orders the headlights turned on and Sulu obliges. It takes a long time to get this ship actually moving and out the door. The movie should be taking off, but it’s done so slowly, with Kirk staring at screens and even checking the rear view window — perhaps to see if the plot was following the ship — that it moves like sludge.

A time-distorting wormhole sneaks up on Kirk faster than the plot in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

A time-distorting wormhole sneaks up on Kirk faster than the plot in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

The movie can no longer delay having something happen, but it looks like the filmmakers had yet to figure out the plot, so the wormhole sequence is dropped in like filler. Even more amazing, the big threat from the wormhole is that it slows down time. In a movie that’s struggling to find a heartbeat, it’s hilariously apt, even at the same time it looks pretty cool. The weird jiggling motion everyone does, but especially on Ilia, reminds me of the sequence in Airplane! with the line, “She’s starting to shake! She’s starting to shimmy! … ” Some of this approach to danger appears to come from Gerrold’s criticisms in his book The World of Star Trek, where he argues for scientific accuracy and the drama of a countdown as opposed to explosions rocking the actors out of their chairs.

Kirk takes criticism from McCoy and Decker in stride.

Kirk takes criticism from McCoy and Decker in stride.

Livingston earns some of his paycheck here by tying all this into Kirk’s rather limited character arc for the movie. He pushes the crew to warp speed before they’re ready — we know this because McCoy literally tells him so — and then Decker has to come to the rescue because only he knows the new ship well enough to get them out of it.

This is rehashed in a decent sequence in Kirk’s quarters as Decker speaks his mind and McCoy backs him up. It’s well shot, well directed and well acted. The biggest difference between Decker and Riker is that the former is more confident — he’s already made the rank of captain and being demoted frees him up to criticize Kirk in ways that Riker never would have dared with his admiration for Picard. Kirk doesn’t come off well in this — he’s pretty clearly obsessed with regaining control of the Enterprise and Bones is correct in that it blinds Kirk to more important priorities. This idea came up more than once in the original series, but usually in a way that was flattering to Kirk and his devotion to the mission. Here, it’s a defect and a bit of a downer.

The orange-colored corridor on Deck 5 for the scene in which Ilia and Decker talk always has and always will remind me of an episode of “The Love Boat” I saw as a kid in which Captain Stubing was trying to get a specific, obscurely named color of paint for the Lido Deck. This scene would not have been out of place on that show. (And wouldn’t Roddenberry have loved to “cast” Charo on Trek.)

Thankfully, the wormhole incident has slowed down the plot enough for Spock to catch up with the Enterprise 45 minutes into the movie. The feature-level makeup for Nimoy is excellent, and Spock looks better and more alien than ever in his return to the bridge. There’s a weirdly corny bit here with the crew’s reaction to seeing Spock: Uhura gasps, Sulu says “Why, it’s Mister …” and Shatner completes it with “Spock!” And then repeats “Spock!” like he can’t think of any other words.

Leonard Nimoy sports an updated and much improved look for Mr. Spock.

Leonard Nimoy sports an updated and much improved look for Mr. Spock.

Spock, of course, is a superstar. And everyone defers to his magnificence, including Decker. With Spock in charge, they get the warp drive working well. I always liked the warp effect in this movie, with the rainbow refractions and swirling stars. It was altered for the later movies, but this one is the sharpest.

Spock, Kirk and McCoy catch up in the fancy new officer’s lounge aboard the USS Enterprise.

Spock, Kirk and McCoy catch up in the fancy new officer’s lounge aboard the USS Enterprise.

The scene in the officer’s lounge is a good one, with Spock explaining himself to Kirk and McCoy. It works because there are obvious conflicts at play here, but it’s not until the end that the script goes completely on the nose. But the dialog is good and it’s well acted. Remember that, because it’ll be a while before you see it again.

And here’s where Roddenberry’s novelization weighs in with some real weirdness. After solving the warp drive issues, Spock heads off to meditate in the section of the Enterprise where crew members go for quickies.

Spock made his way to the extreme forward area of the engineering hull. It was here that a labyrinth of forcefield generators and spider-webbed hull supports provided a maze of odd-shaped cubicles which some architect-psychologist had designed into comfortable and private alcoves, each with its individual view of the stars. This was in some ways the most pleasant area of the starship, being as it was a casual design afterthought and without the purposeful efficiency of the rest of the vessel. It was popular as a place for the many pleasures which a crew member might find in solitude or in new friendships.

As he entered, Spock’s ears caught the sounds of humans at love, which told him that privacy was still respected in this area of the ship. He moved quickly on, wishing his hearing was not so acute at times like this — it was the beginning of coupling he had heard and it distracted him. Odd this human need to continually rub this and that part of their bodies together, particularly since humans conducted it while fully rational, sometimes even intermixing it with conversation, which was certainly far from any definition of passion by Vulcan standards.

— Pages 125-126, “Star Trek: The Motion Picture — A Novel” by Gene Roddenberry, Pocket Books, first printing, December 1979.

Imagine trying to get that past the NBC censors.

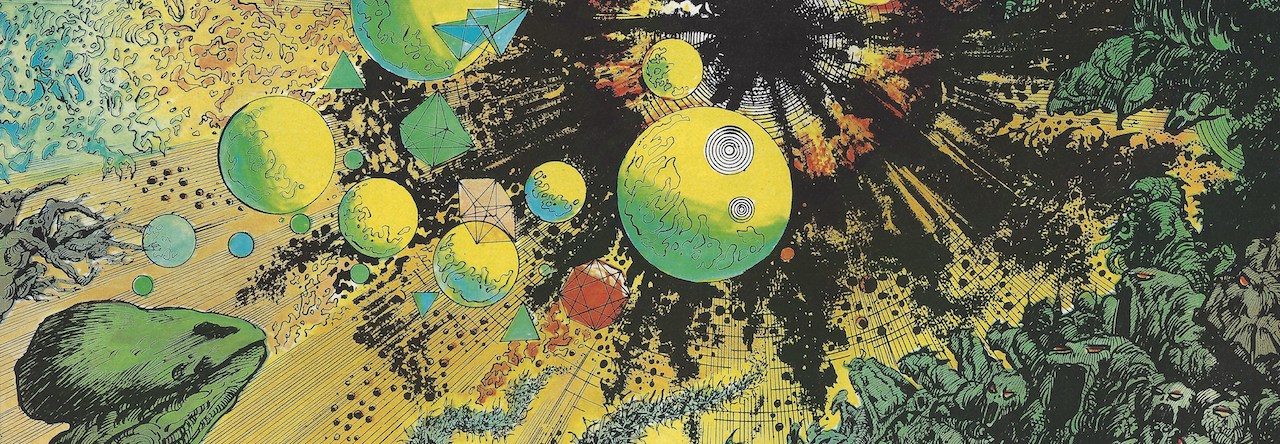

The USS Enterprises cruises over the surface of the alien V’ger.

The USS Enterprises cruises over the surface of the alien V’ger.

Fifty-five minutes into this movie and the Enterprise has finally intercepted V’ger. For some reason, it reminds me of the scene in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, where you start to think that, thanks to Soviet technology of the time, Kelvin is going to drive to the alien planet and you’re going to watch it in real time. But at least we’re finally here. Commence the plot!

The Kirk-Decker exchange is good — Kirk is changing. Spock’s connection with V’ger is deeper and more telepathic than previously shown. The second probe attack has some weird timing issues and apparently a missing sound effect that makes the probe’s lack of impact anticlimactic. I’m sure Roddenberry came up with Kirk’s weird self-adjusting chair, which looks like it’s designed to cover up unwanted erections more than anything else.

George Takei tries to figure out what Lt. Sulu is looking at on the bridge.

As the Enterprise penetrates V’ger, it’s just weird to watch Ilia and Sulu staring at the screen with no idea what they’ll be looking at in the finished film. The images are in some cases very good and interesting and in others less so. The first view of V’ger is of a very yonic (look it up) structure. The images of the ship itself are much better than those in the cloud. But the movie is still yawning along at a terribly slow pace. We are now 72 minutes in as we see the mushroom and complete the first flyover of the V’ger ship.

V’ger’s probe attacks Spock while Ilia realizes she’s about to be written out of the movie.

V’ger’s probe attacks Spock while Ilia realizes she’s about to be written out of the movie.

I’ve always wondered about this strange effect during the scene where the probe is on the bridge. There’s a distortion around the vertical column of light that makes it look like the background behind it has been stitched together imperfectly from two separate images. I like Chekov’s line: “Absolutely I will not interfere!” And I think the images on the bridge monitor screen as V’ger scans the computer are from the Star Trek blueprints set you could buy in the 1970s. There is a bit cut from the sequence in which one of the security guards gets zapped. And it really is unclear why the probe chooses Ilia to digitize and store instead of, say, Spock, who smashed the computer to stop V’ger’s scan. Maybe the probe is a male and was attracted to her pheromones. Decker shows his potential as a series character with that final line: “This is how I define unwarranted!”

But before we can even miss Ilia, V’ger’s anus puckers up and sucks in the Enterprise. The biological look of all this stuff can’t be unintentional, but did it have to be so strangely graphic?

Chief DiFalco, who takes over the now-toasted Ilia’s navigation duties, is played by Marcy Lafferty, Shatner’s wife at the time. Spock’s line foreshadows the Borg: “Any show of resistance would be futile.” (The Borg and V’ger would likely get along like Deltans at a school meet and greet.)

And then Ilia’s back — in the shower, of course. They call it a sonic shower, but she’s clearly wet, so it’s not clear what the difference is. And how does that bathrobe appear?

Ilia steps out of the sonic shower wet and fully dressed. What?

Ilia steps out of the sonic shower wet and fully dressed. What?

It’s 84 minutes in and Ilia mentions V’ger’s name — the first time we hear it — and its desire to join with the creator. Pixar movies can evoke an entire range of human emotions in that time frame. And, once again, as Ilia is examined and it’s revealed every function of her body is duplicated in exhaustive detail, it becomes clear that this movie’s focus on exploring the unknown includes as primary concerns: What is this alien life form, and can we fuck it? And there’s no clearer acknowledgement of time’s passing and Kirk’s “maturing” in this movie than the machine’s preference for Decker.

Next: The rest of the movie, and the answers to the questions everyone is asking!