Which brings me to Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko (Fantagraphics, $39.99), in which author Blake Bell examines the life and work of one of comics’ greatest enigmas.

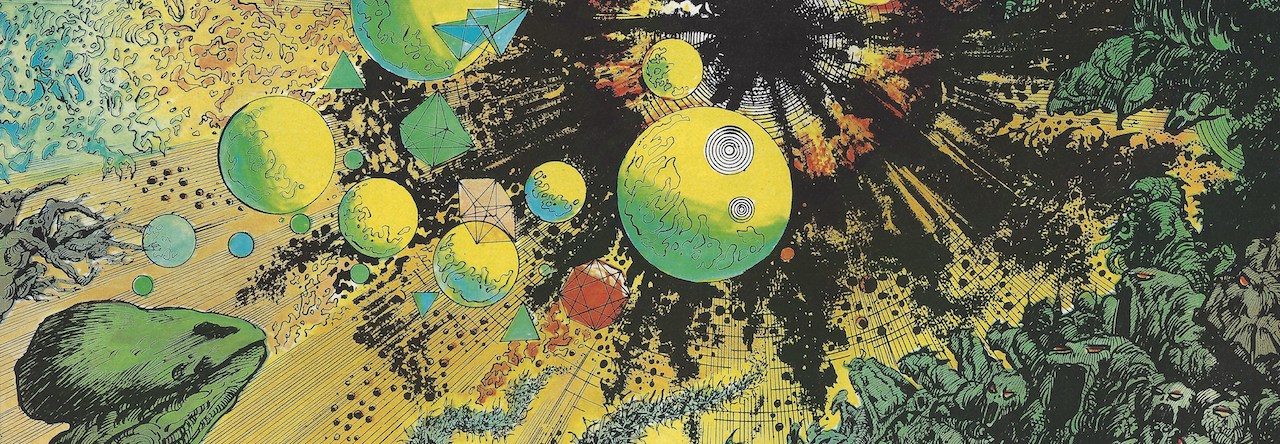

Almost anyone interested in superhero comics knows Ditko was the artist who co-created The Amazing Spider-Man and Doctor Strange with Stan Lee. Those who go a bit deeper will know that Ditko also created some cool characters at DC Comics in the late 1960s and 1970s, including The Creeper, Hawk and Dove and Shade, The Changing Man. A few more willl remember him for doing layouts on the cult 1980s Marvel series Rom, and a dedicated few will have perused Ditko’s independent creations such as Mr. A. But given that Ditko has refused to be interviewed or appear in public for decades now, little else is really known about this artist, who created some of the most unnerving and interesting comics in the medium’s history.

Bell does the best job of any attempt I’ve ever seen to bring together everything we know about Ditko’s life and work. The result is fascinating, frustrating and eventually presents a sad portrait of an immense talent that withdrew from the world and denied it of his work and himself of the audience, acclaim and success that was easily within his grasp.

Unlike Jack Kirby, Will Eisner and most of the artists that broke into comic books in the so-called Golden Age, Ditko always wanted to work in the field. He was part of the first generation of comic book fans, specifically seeking out work and a career drawing and writing stories like those they had admired as children and fans. Both the quantity and quality of Ditko’s early comic book work surprised me. The glimpses Bell offers of the 1950s stories for Charlton and the company that would become Marvel are fascinating and have a quality that makes the idea of tracking down the best of those tales very attractive.

Where the tale of Ditko’s career starts to go off the rails is in the early 1960s, when he starts subscribing to the philosophy of Objectivism as put forth by author Ayn Rand primarily in the novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged. I got about as far into Rand as I did with L. Ron Hubbard’s Mission Earth, and stopped reading the book before getting through even 100 pages of her preachy, boring and profoundly awful worship of fascist ideals.

The specifics of Rand’s philosophy aside, Ditko obviously found something in it that, at the very least, obsessed him. Obsession is a common theme with comics — fan is short for fanatic and everything about comics from the collecting to continuity to trivia to cosplay evokes some level of obsession. Whether there’s a direct connection, I doubt we’ll ever know because there are so few details about Ditko’s life, even in a book as relatively thorough as Bell’s.

It’s almost impossible to imagine, given what little we know, that Ditko hasn’t spent most of the last 40 or so years in the same studio with little to no contact with the outside world. No mention has ever been made of him having sustained a romantic relationship (though Will Eisner said in Eisner/Miller that Ditko has a son), or enjoying much of anything outside of ruminating over Rand or drawing comics.

It’s not like Ditko has been completely silent, though he mostly has put his side of things out in letter and essays that disallow any kind of direct questioning. I was similarly annoyed and frustrated by Ditko’s lengthy essays in The Comics newsletters (passed on to me by Batton Lash shortly after I served as a judge for the Eisner Awards a few years back). He’s also written letters of protest to various magazines and writers, though he never makes himself available to answer questions. I found it odd that Ditko has no problem lambasting Stan Lee in writing but, according to an episode Bell recounts, got along famously with Lee at their last meeting to discuss a potential comics project sometime in the early 1990s. Does Ditko lack the courage to voice his convictions in a public forum, where he and his ideals can be tested and questioned?

I truly hope not, but it’s hard to argue that Ditko’s adherence to Objectivism hasn’t cost him dearly. He’s passed up chance after chance to continue to make comics with impact, that speak to and entertain a wide audience while bringing him more personal acclaim and financial success than he’s found doing his small-press rants.

Nothing would make me (and, I’m sure, Bell) happier than for Ditko to come forth and answer some of these questions. Unfortunately, that seems highly unlikely, leaving only the chance that some clues to his life and work will come to light only posthumously.