“Secret Six” #1 (May 1968) is half a good comic.

There are no credits in the issue, but the indicia lists Murray Boltinoff as editor and a text page features bios of artist Frank Springer and writer E. Nelson Bridwell, so that’s the basic team for this new bimonthly series that would have arrived on newsstands sometime in early 1968. The book makes a big pitch for readers to plunk their 12 cents for this comic with the cover, which is the first page of the story and includes the pitch right there for all to see:

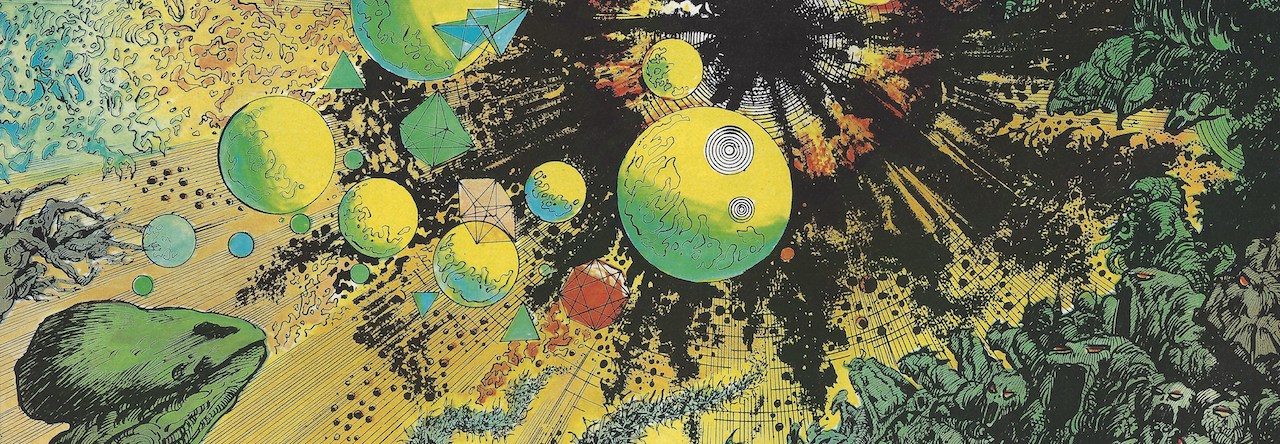

Cover to “Secret Six” #1, May 1968. Art by Frank Springer.

The cover kicks the story into high gear, rapidly introducing an interesting cast of characters. The first pages shows the crash on the cover was a stunt for a movie, pulled off by King Savage, who promptly ditches the set for a more important call. The next two pages introduce the five remaining characters and does so quite well as long as you don’t think too hard about any of it.

Take Crimson Dawn, who in a single introductory panel is revealed as a top model working the runways of Paris only to later have Mockingbird explain a few pages later she’s an heiress who fell in love with a con man who took all her money and was “glamorized” so her family would be unable to recognize her and, presumably, be able to get revenge on her. If you’re confused by that, just wait.

“Uncanny” Carlo di Rienzi is a famous illusionist who vanishes on his own act when Mockingbird calls. The act itself is an unclear mess. He appears to trade places with an assistant locked in a crate, but the panel shows the assistant suddenly standing on stage where di Rienzi was standing while in full view of there audience. How was this supposed to work, given there’s no typical comic book magic at play?

Also getting one-panel intros are August Durant, who appears to be one of the United States’ top atomic scientists, and Lili de Neuve, a hairdresser/masseuse in high demand among the ritzy ladies who frequent the French Riviera. Lastly, there’s Mike Tempest, who’s tossed out of a rundown cafe on the Marseilles waterfront for being unable to pay the check. There’s a dramatic assemblage, in which the reader has to endure such scintillating dialog as “Silence! Listen, … do you hear a plane?” followed by a panel featuring a strange looking military-style craft and someone shouts “An airplane!” as though the sight of one is more rare than Bigfoot. And then we get more back story and Mockingbird’s hold over each is revealed: Durant was infected with a fatal disease by a foreign power and needs the cure only Mockingbird can provide; Tempest was the top boxer know as Tiger Force before his refusal to throw a match led to his testifying in court against mobsters who beat him severely and would kill him were Mockingbird to tip them off; di Rienzi also defied the mob, which killed his wife and injured his son, who will walk again one day thanks to the treatment Mockingbird so graciously provides. Then on page 9, the final three, including Crimson Dawn, get their due in a single half-page panel: de Neuve was framed for murder and would still be in prison were it not for the alibi Mockingbird provided, while King Savage was an ace pilot in Korea who was captured and talked to the enemy and would be branded a traitor were it not for Mockingbird arranging both an escape and a life-saving warning of enemy movements that earned King the title of hero. Adding to the cramped intensity of all this is the half-page advertisement on that very same page 9 for a Monogram hobby kit of a strange looking vehicle called Beer Wagon.

There’s a lot to unpack in these first nine pages (10, if you count the cover). The underlying premise of this group of odd characters with somewhat sordid skeletons in their closet being blackmailed into performing espionage missions is really quite compelling. That one of the team members is also the mysterious blackmailer is also a really cool idea. But both of those ideas require some real skill to pull off well and, to be frank, Bridwell’s script is not up to the task. The quickly drawn sketches of these characters is squirelly in the extreme and falls apart like wet tissue paper under even the most basic scrutiny. But there are still interesting moments, mostly held up by the quality of Springer’s art. The cover intro is effective and a technique that I’d think more comics, aside from Watchmen, would use. Springer’s staging is really effective and his art has some nice detail even if his characters are a little stiff looking. The standout segment is Tempest’s origin, which is moody and a good shade more violent in a realistic way than the rest of DC’s output at the time. Springer also gives Durant, di Rienzo and to some extend de Neuve a convincing physical identity that makes them immediately identifiable throughout the story.

Page 11. Try not to laugh at the vacuum plane!

Remember where I said this was half a good comic? We’re now getting into the other half, a strange tale that makes even less sense than the first half and is likewise held up by a few passages in which Springer’s art finds a way to make it all seem cool. Page 11 sets up the mission: There’s a man named Zoltan Lupus, who spent all his considerable wealth on an invention that sucks the oxygen out of the air. The drawing of the weapon looks like a Transformer who converts from an airplane into a vacuum cleaner, and this idea of vacuuming the oxygen out of the air and suffocating people in the villages below is almost impossible for a rational brain to process. Zoltan, who looks like the singer for a heavy metal band at age 80, also has set up his own nation on an island that once was home to an escape proof prison. His plan is to get funding to finish his weapon from four wealthy businessmen and then use it to blackmail the world into doing something the story never explains. Anyway, the businessmen coming to the island provides the opportunity for the Secret Six to get inside and stop Zoltan from doing his thing.

As I said above, the premise of the series requires the plots to be highly dextrous and intricate to work. Unfortunately, “Secret Six” lacks the imagination to pull that off and goes instead for Crimson cozying up to one of the businessmen and slipping a drug in his drink so Tempest can be made up by de Neuve to pass for him and basically walk inside. This works, and the rest of the team either is smuggled in via crates of key equipment or by the tried-and-true method of going in via the sewars. The latter provides a few interesting moments with Di Rienzi and Crimson swimming into a pipe and finding an unexpected grate blocking their way. Di Rienzi panics but Crimson produces a bobby pin that the illusionist can use to remove the screws holding the grate in place. The sequence end on another half page, but it’s a nice half-page with a two-panel sequence in which Crimson and Di Rienzi emerge from the tunnels to find their captors waiting.

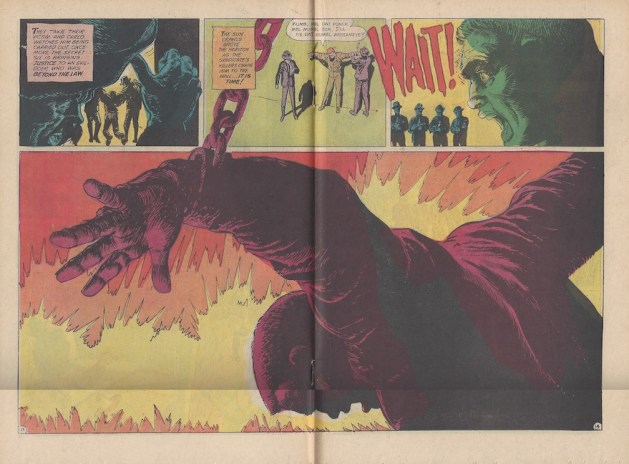

Things get confusing and weird for a few pages. Then Durant is revealed to have been captured and awaits death as the subject of a test of Zoltan’s vacuum machine. Springer delivers a rather striking panel taking up two-thirds of page 18 of Durant, in shadow, awaiting his fate amid some funky looking machinery that looks like one part is built with a smiley face over a water fountain. This is followed up by another nice sequence of Durant as the machine injects laughing gas into the room instead of sucking out the oxygen. There’s a big fistfight that makes little sense, with Tempest coming face to face with a henchman he recognizes as one of the men who beat him up in his origin sequence. Everyone gets out and the next adventure is teased.

One thing that occurs to me after reading this issue is the credits on these issues list Joe Gill as writing dialogue, suggesting the book was created Marvel style. That would have been radically different for DC in 1968 and shows some of the shortfalls that come from that approach — namely that it’s great when the writer and artists connect, and a real mess when they don’t.

Next issue: Things get worse before they maybe get better?

Like this:

Like Loading...

“Secret Six” #6 (Jan. 1969). Art by Jack Sparling.

“Secret Six” #6 (Jan. 1969). Art by Jack Sparling.

Page 2

Page 2

Page 10

Page 10

Page 13

Page 13

Page 16

Page 16

Cover to “The Comic Book Heroes,” by Will Jacobs and Gerard Jones. Published by Crown Publishers in 1985.

Cover to “The Comic Book Heroes,” by Will Jacobs and Gerard Jones. Published by Crown Publishers in 1985.