I’ve long wanted to get back to writing about comics on this blog.

I’ve been especially inspired of late by the Cartoonist Kayfabe channel on YouTube. If you like comics and aren’t watching this, I highly recommend you check it out now! The channel is run by Pittsburgh-based cartoonists Jim Rugg (“The Plain Janes,” “Street Angel,” “Aphrodisiac”) and Ed Piskor (“Hip-Hop Family Tree,” “X-Men: Grand Design”), and they run through a lot of great comics history and interview some of the real greats of the business in a unique way. What strikes a chord for me is the channel’s love of comics as comics — not corporate IP being held in check for an eventual movie — this is just about comics and the work that’s on the page. And they also understand that comics are best when they are a subversive medium, and so the focus is often on the most critically acclaimed works, like Alan Moore’s “Miracleman,” and the best indie comics of yesteryear and today. It’s the sort of thing that makes you long for the days when you had hours to spend diving through quarter bins at your local comic shop or convention to find those treasures that the speculator crowd (which seems to have made a big return of late) would never pick up or understand.

This approach has definitely affected my comics reading of late and I’ve been thinking more and more about those hidden gems and wild, almost-forgotten experiments. So up first is a short-lived DC Comics series from more than 50 years ago that I’d long wanted to check out and finally have: “Secret Six.”

My introduction to “Secret Six” came not in the pages of any comic, but a book about comics. “The Comic Book Heroes,” published in 1985 and written by Will Jacobs and Gerard Jones, was extremely influential on me.

Cover to “The Comic Book Heroes,” by Will Jacobs and Gerard Jones. Published by Crown Publishers in 1985.

Cover to “The Comic Book Heroes,” by Will Jacobs and Gerard Jones. Published by Crown Publishers in 1985.

I first saw a copy shortly after my family had relocated to Arizona, on a shelf in the back of a Waldenbooks outlet in Paradise Valley Mall. I lacked the cash to fork over the $11.95 cover price as I preferred at the time to put my limited expendable resources into buying comic books themselves. But I seemed to spend a lot of time at the mall and was able to read a decent portion of the book before it was bought by someone else or remaindered.

I didn’t acquire my own copy until 1989, when I was a journalism student at the University of Arizona and found a copy at Bookman’s, a huge used bookstore that to this day remains one of my favorite places ever to just hang out. I know I read it more than once, probably more than twice in the first few months I owned it.

This was a book that really put into perspective the comic book industry I knew. The books on comics I had previously found in libraries and bookstores focused almost exclusively on the Golden Age, an era that at the time seemed far away and completely inaccessible without access to the tons of cash that would be required to become well-read in any part of that era. Jacobs and Jones instead started with the Silver Age, running up comprehensively through the 1970s and putting an early spin on the heady expansion of the direct market in the 1980s up to the book’s publication.

The book also was vastly entertaining, examining the content of the most impactful stories of those times and also talking about the creators and the business goings-on behind the books. While Silver Age books also were mostly beyond my budget, “The Comic Book Heroes” nonetheless sparked an interest in reading and experiencing the comics its authors wrote about with love, passion and knowledge.

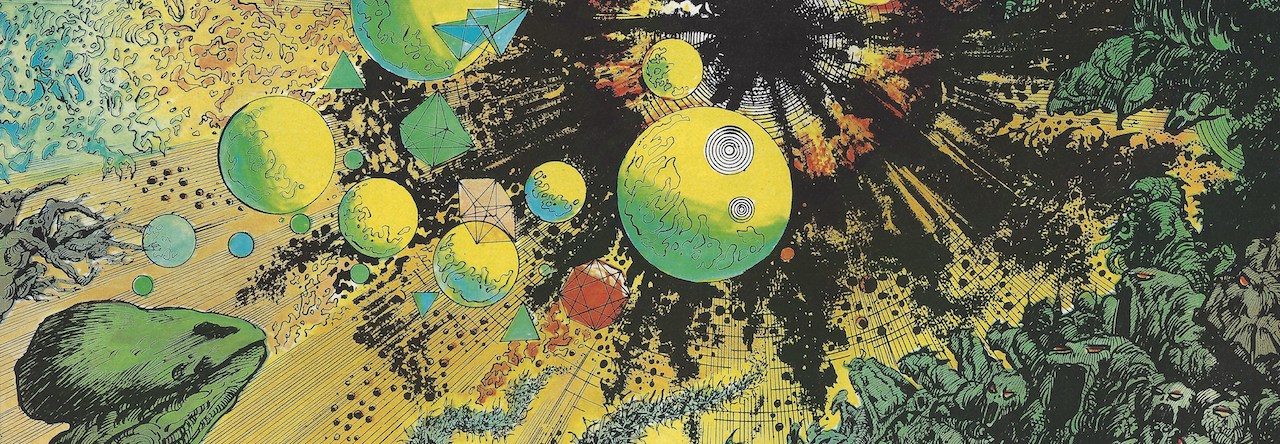

Chapter 18 is titled “The DC Experiment,” and devotes eight pages of text and two pages reproducing interior pages from “The Hawk and the Dove” #5 and “Secret Six” #4. The book covers what the authors write is an intense period of experimentation that came about after the Kinney Corporation conglomerate bought DC in 1967 and added it to its roster of funeral homes and parking services. Run by Steve Ross, Kinney would soon acquire Warner Communications and bring DC under its umbrella. But first, the new management had to face of sluggish sales and the rising threat of Marvel.

Seeking an editorial director who could unite the fiefdoms that editors like Mort Weisinger and Julie Schwartz had long rule, DC’s new owners tapped freelance artist turned DC cover editor Carmine Infantino for the job. Infantino’s experience as an artist instead of a writer or businessman made him an unusual choice, and he quickly took advantage of the new role to bring in veteran artists as editors and let them loose to innovate some new titles. Among those new editors was Dick Giordano, who had previously been executive editor at Charlton Comics when it was putting out some of its better titles, like “Captain Atom,” “Blue Beetle” and “The Question.”

The titles comprising the DC Experiment of the chapter’s title included short-lived but well-regarded series such as “The Creeper,” “The Hawk and the Dove,” “Bat Lash” and, of course, “Secret Six.” Jacobs and Jones wrote an entire page on “Secret Six,” noting the obvious inspiration of the hit TV series “Mission: Impossible” before spending a pair of lengthy paragraphs explaining the premise, characters, and how the series’ relatively realistic tone eschewed aliens and superpowers for an approach flavored with gritty pulp elements. They hail the “excellent quality of the strip” and lament that its short, seven-issue run failed to resolve the main premise, which as of that writing had yet to be revisited.

So with all that running around in your head, how could you not want to read this comic?

It took many years for me to acquire the seven-issue run, mostly picked up whenever I stumbled across one in a comic shop or convention bargain bin. I finally finished the run last year, and even more miraculously managed to assemble all seven issues in one place so I could read them.

And now I have.

Next, I’ll delve into the fascinating mess that is “Secret Six” #1, and from there we’ll see how well it hold up 52 years later. Stay tuned.

Leave a Reply