Wednesday Comics (DC Comics, $49.99, 200 pages) is even more impressive to look at in the spiffy new oversize hardcover edition. The strips read much better (and more quickly) grouped by feature than they did one page a week.

The quality of the strips is overall pretty good, but they obviously are not equal, so here’s a strip-by-strip rundown of this very cool comic.

Batman, by Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso, kicks things off with a slight disappointment and is not as good as I was expecting given the creators. A basic detective story whodunit in which a banking magnate dies and the suspects include his son and his trophy wife, is simply serviceable. Risso doesn’t seem to have time to find his legs in the new format and doesn’t have the freedom to cut loose with the sex and violence he draws so well.

Kamandi, by Dave Gibbons and Ryan Sook, is a flat-out tribute to Prince Valiant and its peers in the classic adventure strips genre. Gibbons eschews balloons and scripts the story Prince Valiant style, with blocks of text that combine both narration and dialog. And it works extremely well with the classic look of Sook’s artwork. The lush, illustrative art deviates radically from the iconic Jack Kirby version, but Sook sells it with detail and elegance.

Superman, by John Arcudi and Lee Bermejo, is a gorgeous looking comic that combines old-school illustration with terrific modern coloring. I saw some of these original art pages at San Diego last year, and Bermejo and colorist Barbara Ciardo deserve credit for the best-looking Superman comic in years. The story mixes the action with the human side of Clark Kent to mixed results, though I can’t say the fault lies with Arcudi entirely as DC has for years focused on the man at the expense of the super when it comes to the Man of Steel. Fans of today’s Superman comics will dig it; the rest of us can just look at it and drool.

Deadman, by Dave Bullock and Vinton Heuck, was a lot of fun to read. As someone who’s never read a Deadman comic before (though I would like to read the classic Neal Adams run), the wise-cracking characterization of Boston Brand was unexpected. Bullock, who comes from the animation side of Warner Bros. and directed the very cool Justice League: New Frontier home-video adaptation, injects a lot of energy and fun into the kind of karmic life-after-death story that is so dreary in the wrong hands. Of all the strips, this one surprised me the most and I would read more of Bullock and Heuck on this character.

Green Lantern, by Kurt Busiek and Joe Quinones, is a pretty standard GL story that stands out visually because of the retro, Space Age setting. I like the idea of Hal Jordan as a test pilot during the era of Chuck Yeager and the Mercury astronauts because that’s really the only time in American history where those men were well known and admired as heroes. I wish the storytelling had been a bit more inventive, but it works just fine as is.

Metamorpho, by Neil Gaiman and Mike Allred, sounds like one of those can’t-miss team ups. And while it looks great and the story has some nice details in it, it doesn’t blow the doors off the way I was deep down hoping it would. As always, Allred’s art shines and is gorgeous to look at. He doesn’t go overboard with experimentation, but he does try some very cool tricks, primarily the “Snakes and Ladders” game board and Metamorpho and Element Girl hopping through all the elements of the periodic table in a huge two-page spread. The problem is these tricks don’t come off as an organic part of Gaiman’s story, which features a rather plain plot and some really fun wordplay in the periodic table pages especially.

Teen Titans, by Eddie Berganza and Sean “Cheeks” Galloway, is one of the harder strips to follow as both the story and the art confuse. Berganza’s tale is a pretty standard superhero story that would be well-suited to an episode of the cartoon series. Galloway is an excellent artist and a fantastic character designer whose work on such animated series as The Spectacular Spider-Man is top-notch. But the layouts used in this format are extremely confusing, muddied even further by using anime-style muted coloring. It looks better in the collected edition than it did on newsprint, but still seems like a poor choice when brighter colors and stronger contrasts could have made this really pop.

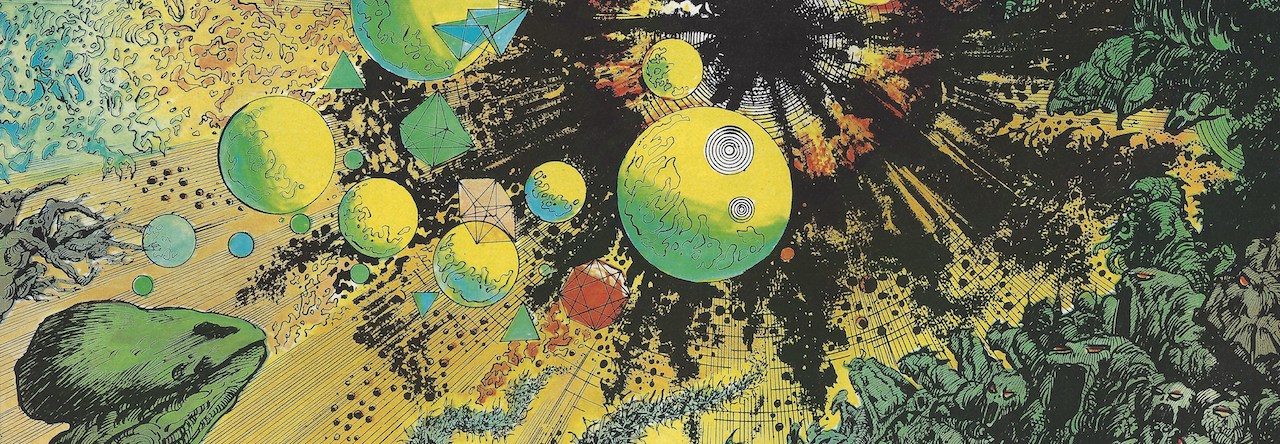

Strange Adventures, by Paul Pope, picks things up again. Pope is exactly the sort of artist whose style and design sense really play into the broadsheet comics idea. The story, which stars Adam Strange, is again a pretty standard Adam Strange story, but the joy comes from the way in which Pope draws this familiar character and his worlds in a way that completely recasts it as more Heavy Metal and less Murphy Anderson. If Paul Pope drew a dozen science fiction comic books a month, I would buy them all.

Supergirl, by Jimmy Palmiotti and Amanda Conner, is the must purely fun strip in this collection. The story shows Supergirl chasing after Krypto and Streaky as they chase each other and playfully cause their share of super-size damage. Conner really has a knack for the story, and for the first time I can remember Supergirl is a enjoyable and cute character without being hyper-sexualized. Paul Mounts, who colored this story, also deserves a pat on the back for giving it a bright, clean look that really pops off the page.

Metal Men, by Dan DiDio and Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez and Kevin Nowlan, was a real pleasant surprise. I know that Garcia-Lopez is revered in comic art circles and is to many professionals the best artist in the business, but I haven’t had much chance to ever read much of his work beyond, I think, an arc or two of Legends of the Dark Knight. But his reputation is certainly supported by the outstanding artwork here. Not only is everything well drawn, but the scenes are beautifully composed and the pages laid out to take maximum advantage of both the format’s ability to display both big iconic images and pack in a lot of story. I always found the Metal Men a little too goofy to read a long run of stories about them, but this was just right.

Wonder Woman, by Ben Caldwell, is the lightning rod tale of this book. Like Galloway on Teen Titans, Caldwell uses a distinct but subtle color scheme that made deciphering the sketchy, small-panel art style almost impossible on newsprint. The collected edition is a big improvement, and I found a lot more to like in the dream-like story than before. It still is my least favorite strip in the book, however, though I applaud Caldwell and DC for being willing to experiment like this with such a high-profile character.

Sgt. Rock and Easy Co., by Adam Kubert and Joe Kubert, is a real old-fashioned DC war comic story that works as entertainment even though it doesn’t break any new ground. Joe Kubert’s art is, as always, outstanding and instantly recognizable. No one can do this kind of material as well as he can. The story is solid and stands solidly within the tradition of Sgt. Rock stories, which also makes it very old-fashioned and perhaps a little stodgy given that World War II ended 65 years ago.

The Flash, by Karl Kerschl, Brenden Fletcher, Rob Leigh and Dave McCaig, is the best superhero strip in the book by a long shot. It’s also one of the best and most memorable Flash stories I’ve ever read, perhaps because the plot is willing to take its premise all the way to a conclusion that’s both logical and satisfying. There’s a lot of little things to like, such as including a separate Iris West strip in the old romance-comic style and even a Gorilla Grodd sequence that’s a nod to old Tarzan comics. This one also does some of the coolest bits with the broadsheet page, designing sequences of panels that easily lead the eye all over the page in patterns that would render most other comics unreadable. This is a very appealing take on the Flash, and I wish that the character’s new comic book series had even half the panache of this version.

The Demon and Catwoman, by Walter Simonson and Brian Stelfreeze, is a strangely bloodless exercise. Stelfreeze is a good artist, and he delivers the kind of solid drawing and polished inking that I would like to see in more superhero comic books. But there’s not as much experimentation or playing to the format here. Simonson’s story is solid, but similarly doesn’t do much to make me care about these characters or showcase the pairing in such a way that it makes me want to read more.

Lastly, there’s Hawkman, by Kyle Baker, which is expectedly hilarious. Baker just pulls out all the stops and turns the character into the ultimate macho superhero who responds to the weirdest plot twists by just hitting everything as hard as he can. The opening page, which parodies Frank Miller’s 300 comic with “We flap!” replacing “We march!,” is a riot. The art is similarly ripped, with what looks like computer models and photo referencing producing every kind of macho detail a fanboy could want. All this, and it never takes itself seriously! I love it.

This edition wraps with two single-page strips that I imagine didn’t make the cut. The first is a cartoony Plastic Man strip by Evan Dorkin and Stephan DeStefano, the second is a Creeper page by Keith Giffen and Eric Canete. I can’t say either impressed me enough to want to see more, though I would definitely try a Dorkin and DeStefano superhero comic.

The Wednesday Comics experiment falls into the success category. Even though not every strip succeeded, the experience of reading the book was a satisfying one — moreso than reading the strips in the original serialized form. A big part of that for me is the variety of the strips — no two strips were alike; no two creative teams experimented with the format in quite the same way. More than anything, Wednesday Comics is adventurous in a way that DC would do well to try spreading to the rest of its comics line.

Like this:

Like Loading...