Watchmen is not the movie I was hoping for. There’s a lot of reasons for that and it hardly means there’s not some really great stuff in there or that many fans of the book won’t love it completely and unapologetically.

But for me, even though this is a film that does a very good job of squeezing all the plot points from the comic into movie form, the tone, scope and underlying world that made the book so convincing and compelling is missing.

The tone was the most jarring element for me. And I’m sure a lot of it has to do with the fact that I’ve read this book and interpreted in my own way for more than 20 years. But it’s hard to reconcile the deliberateness of Dave Gibbons’ images and Alan Moore’s immaculate pacing with the very average performances and staging of scenes in this film.

This comes down to more than the actors, whose performances nevertheless will be debated endlessly by fans of the book. By far the best is Jackie Earle Haley as Rorschach, who delivers on the obsession and a pitch-perfect gravelly voice. It’s a shame his face isn’t seen for much of the film, but it’s still a top-notch turn. I can’t say the same for the rest of the cast, whose only crime seems to be that they seem too young for these roles and don’t deliver the gravitas in performance or even voice quality that I expected from this movie. Billy Crudup, a very fine actor in pretty much everything I’ve ever seen in him, plays Dr. Manhattan’s voice with an uncertainty that falls short for the voice of a god-like being. Same holds true for Matthew Goode as Ozymandias, though I thought he fit the character much better as the movie progressed. Patrick Wilson and Malin Akerman are who we spend most of the film with, and they’re far from terrible but again don’t deliver the gravitas or convey the inner conflicts of their characters with half the believability that Gibbons’ artwork did.

This comes down to more than the actors, whose performances nevertheless will be debated endlessly by fans of the book. By far the best is Jackie Earle Haley as Rorschach, who delivers on the obsession and a pitch-perfect gravelly voice. It’s a shame his face isn’t seen for much of the film, but it’s still a top-notch turn. I can’t say the same for the rest of the cast, whose only crime seems to be that they seem too young for these roles and don’t deliver the gravitas in performance or even voice quality that I expected from this movie. Billy Crudup, a very fine actor in pretty much everything I’ve ever seen in him, plays Dr. Manhattan’s voice with an uncertainty that falls short for the voice of a god-like being. Same holds true for Matthew Goode as Ozymandias, though I thought he fit the character much better as the movie progressed. Patrick Wilson and Malin Akerman are who we spend most of the film with, and they’re far from terrible but again don’t deliver the gravitas or convey the inner conflicts of their characters with half the believability that Gibbons’ artwork did.

The tone continues to the look of the film, which despite however much money Warner Bros. spent on it again fails to convey the depth of this world. New York City never comes alive as a unique place, nor does Ozymandias’ Antarctic retreat, Karnak. In fact, there’s little variation in the size or depth of the sets, either real or digital, and the comic’s sense of expansive space alternating with stifling confinement is lost amid sets that all seem about the same size and fail to elevate themselves above the norm for a sci-fi movie or TV show.

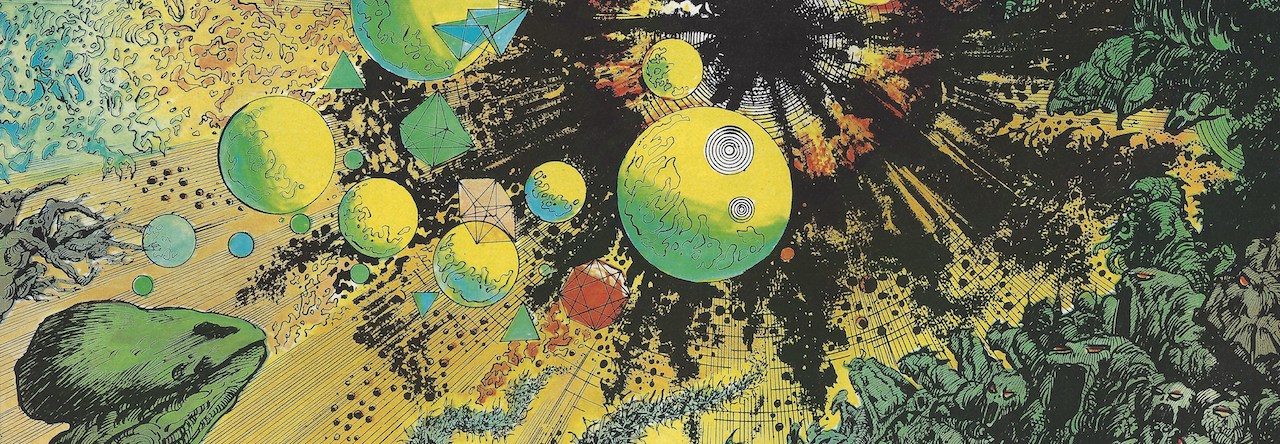

The look of the movie also lacks a certain polish, especially in the visual effects. Dr. Manhattan in particular doesn’t work well. He’s stuck in the uncanny valley, and not even because of the effect used for his blank-glowing eyes, but because he’s too obviously a digital construct given away by rough edges and not being properly composited into a number of scenes. He also moves far too much like a motion-capture demonstration, with the artificial movements of a video-game character and even problems with the lip synch. The Mars scenes similarly are rough around the edges, with the clockwork fortress never appearing clear enough to really understand or appreciate what it was.

It’s the loss of the underlying world that I miss the most. While Richard Nixon gets far more play in the movie than he did in the comic, there was precious little time or attention paid to explaining in any way who these people were and why they were driven underground. In the comic, a lot of that came from the shorthand of the archetypes, but the movie failed to establish especially who Dan and Laurie were, why they became costumed adventurers — even being very clear that they were costumed adventurers who enjoyed what they did very much — and the Keene Act is only mentioned once and even then its rationale was not explained.

And then there’s the big change to the ending — much debated for months in advance. The alternate version makes far less sense than the original ending and is far less dramatic. The sheer audacity and strangeness of the book’s ending, that it was the sort of thing that only a comic book-style villain could come up with, was part of what made it so compelling and interesting. It also, especially after 9/11, would have provided a more convincing reason for the superpowers to pull back from nuclear war, while the movie’s ending would, I think, actually exacerbate the conflict given Dr. Manhattan’s political situation.

The result is a movie that has all the surface elements of a decent adaptation, including pretty much every major plot points, and yet none of the old soul of the book. Moore and Gibbons created a comic that tapped into all the archetypes of superhero comic books and took them to a logical conclusion, building on decades worth of minute details that had built up through the genre and deconstructing them in spectacular fashion. The movie, on the other hand, isn’t really sure what it’s about, other than a trying to stage every scene from the graphic novel in as much detail as possible.

There’s also a lot to debate about the level of violence and gore the film portrays, and director Zack Snyder’s continued use of the fast-slow-fast motion technique made famous in 300. The gore didn’t bother me, though the scene in which the Comedian assaults Sally Jupiter is far more graphic than in the book and a bit tough to watch. Neither quibble had as much impact for me as the other issues. Oh, and the music was awful and completely on-the-nose. I wish they’d used music that actually came out in 1985 rather than hammer home the same Dylan and Hendrix songs that a thousand other movies have used.

There’s also a lot to debate about the level of violence and gore the film portrays, and director Zack Snyder’s continued use of the fast-slow-fast motion technique made famous in 300. The gore didn’t bother me, though the scene in which the Comedian assaults Sally Jupiter is far more graphic than in the book and a bit tough to watch. Neither quibble had as much impact for me as the other issues. Oh, and the music was awful and completely on-the-nose. I wish they’d used music that actually came out in 1985 rather than hammer home the same Dylan and Hendrix songs that a thousand other movies have used.

Talking about it afterward with friends, there were a lot of divergent opinions. The best point was that, despite its flaws, the basic story remains a good one and it’s all in there. Also, given that this was a book long thought to be unfilmable, that this adaptation with its faithfulness to the source material may be as good as anyone could do with this material. Both of which are good points that I’ll have to consider when I next see the film.

Which brings up the next question, of whether and how the director’s cut can improve on this version of the film. I hope it can. I’d like to see more Sally Jupiter, who’s presences seems cut back in the film despite most of her scenes being in there. Also, the death of Hollis Mason — who’s seen early on having his beer session with Dan — would be worth putting in, and perhaps adding some more of the back-story on the Keene Act while they’re at it.

I’ll be most interested to see what people who’ve never read the book think of Watchmen. Most everyone in the press screening at the Grove last night (which was immensely uncomfortable due to a full house and a broken air conditioner) had read the book and most had some serious complaints or problems with the film. But the vast majority of moviegoers haven’t read the book and it would be absolutely fascinating if they found the elements the fans of the book dislike to be reasons why they like the film. That group won’t include critics, who so far have been harsh and, I expect will continue to be harsh given that so many of them dislike comic book movies to begin with.

I’ll be most interested to see what people who’ve never read the book think of Watchmen. Most everyone in the press screening at the Grove last night (which was immensely uncomfortable due to a full house and a broken air conditioner) had read the book and most had some serious complaints or problems with the film. But the vast majority of moviegoers haven’t read the book and it would be absolutely fascinating if they found the elements the fans of the book dislike to be reasons why they like the film. That group won’t include critics, who so far have been harsh and, I expect will continue to be harsh given that so many of them dislike comic book movies to begin with.

As I wrote yesterday, the movie doesn’t change one iota of my feelings about the graphic novel. It’s still among my favorite graphic novels and perhaps the greatest example of what can be done with the superhero genre. But the movie is, at least right now, a disappointment. It’s rare that I find myself revising such opinions for the better, but perhaps on subsequent viewings I will find more to like in this version of Watchmen.

Like this:

Like Loading...