“Experiment in Vengeance!” (22 pages)

Writer: Martin Pasko

Artists: Dave Cockrum & Frank Springer

Letterer: John Costanza

Colorist: Carl Gafford

Editor: Louise Jones

Editor in Chief: Jim Shooter

Cover artists: Dave Cockrum & Joe Rubinstein

This one’s complicated, and not in a good way. I do give Marty Pasko credit for trying to do an issue of the comic that evokes the feel of the show, but this is an excellent example of trying to do a TV show in a comic book format instead of adapting the show to comics.

This one starts off with the USS Enterprise locating the USS Endeavor, a starship lost in action 22 years ago whose fate has puzzled Starfleet ever since. As the Enterprise approaches, Lt. Karen Hester-Jones reports to Kirk as the ship’s new zoologist. She and Kirk have an obvious history together, one that obviously didn’t end well and, for her, not happily. The Endeavor then surprises everyone by intercepting the Enterprise and attacking!

All this happens by the end of page 2!

Page 3 is where the seams start to show. Spock detects no life forms, but the Enterprise is able to immobilize the Endeavor in a panel that sees the word balloons pointing at the wrong ships. The script’s also been all over the place in terms of technobabble, with the Endeavor reported as being found a half-parsec from its last known location (which doesn’t seem that far off in Trek terms), and then distances tossed around inconsistently — 25,000 km out is far out, but then it seems closer at 200,000 before instantly getting down to 1,000 km. A sure sign this issue was under the deadline gun.

It’s interesting to note, as the crew beams over to the Endeavor’s bridge (in environment suits) that the ship’s exteriors and interiors, as well as the crew’s uniforms, evoke the TV series very strongly. With the sweater-like collars on the crew’s tunics, it looks very much like the second Star Trek TV pilot, Where No Man Has Gone Before.

Then it gets weird — and familiar in a not-s0-good way. There’s a mysterious, sparkly cloud that “possesses” one of the crew members. We just had a ghost story in issues #4 and #5, and here we are going down that same path again! There’s a three-page action sequence that’s better than it should be, really, but still fails to be interesting because all the characters are fighting each other in big, clunky, monotone-colored environment suits. It’s a bit of a chore to figure out who’s who in this mess. But they end up beaming back to the Enterprise with the possessed crewman — and the sparkly cloud tags along in the transporter beam.

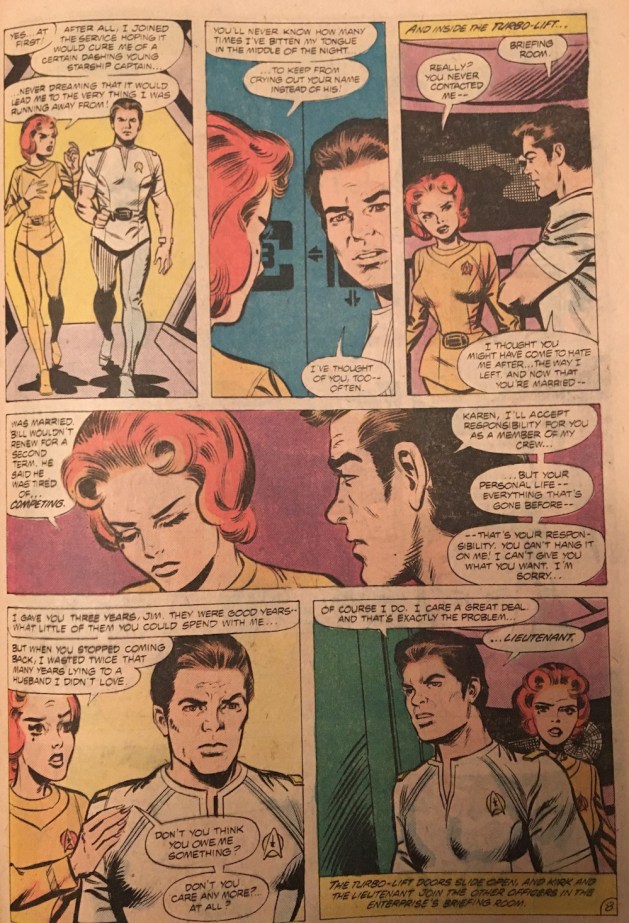

While the sparkly cloud sneaks around the ship, Hester-Jones and Kirk have it out. Turns out they were a couple, until Kirk was drawn back to Starfleet. She was angry at him and married Bill Jones, who realized he couldn’t compete with Kirk and didn’t renew their marriage license. (This was something Gene Roddenberry mentioned in the novelization of Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Marriage licenses in the 23rd century have to be renewed or they expire. Kirk’s marriage to Vice Admiral Lori Ciani ended the same way.) She’s still angry with Kirk, but he has a job to do!

On cue, Spock reveals that the Endeavor’s logs reveal its last mission was responding to a distress call from Janet Hester on a moon called Mycena. Hester-Jones says that was her grandmother’s name, but it couldn’t have been because Janet Hester died at the age of 36 in 2139. Spock then shows it was her, producing a photo of her at age 89. He continues: Shortly after the Endeavor rescued Janet Hester, the crew started going crazy and the crew was eventually murdered or killed by cutting life support. The madness, of course, resembles what happened to the Enterprise crewmember on the Endeavor, so Kirk receives new orders to investigate and orders a course to Mycena.

Ten pages in, you can see how dense this story is, though not in a good way. It’s very episodic and clunky when it wants so very much to be mysterious and interconnected.

And it doesn’t get any better once the Enterprise arrives at Mycena, which is an ice planet. Kirk, Bones, Spock and Sulu beam down in parkas and split up to explore two tunnels that both lead to an underground chamber. Bones and Spock are immediately attacked by a giant lobster creature that resists all phaser fire and can’t be detected by a tricorder. It also has flexible spine, so it can follow Spock and McCoy into the tunnels. Kirk and Sulu somehow spot a human body underneath the ice that isn’t shown in the artwork, and then meet up with Spock and McCoy in a chamber with a device that, when Spock activates it, creates a defense field that keeps out the creature. And if that wasn’t enough, Sulu notices that this alien technology has Starfleet technology added to it.

Then Bones finds some early transporter technology and Spock digs up computer records of the “Hester Project.” Kirk calls the ship, where Uhura is the most-recent crewmember to be possessed. He sends McCoy up to help with that, and orders Hester-Jones beamed down. He asks her to take some samples from the lobster thing and she explains her grandmother “died” when she was lost in space while being transported from the her assignment at the Deneva Research Station. Kirk then realizes she was part of the team that invented the transporter and that, after they were ordered to discontinue the project, she and six of her colleagues ended up getting “lost,” landing on Mycena and continuing their experiments.

You’re not the only one struggling to keep up. The pages stopped even being numbered half-way through this one.

And it gets weirder. The possessed crewmembers all start chanting in unison: “We seek Hester! The Unity seeks Hester!” They then bust out of sickbay, giving McCoy a black eye, and beam down to attack Hester-Jones. Kirk realizes they want Janet Hester and that there are six beings who were all Hester’s colleagues and became trapped as spirit-like creatures because of the transporter experiments. When she was rescued by the Endeavor, they followed and killed the crew trying to kill her. But she escaped in a shuttlecraft and died in a crash landing … on Mycena.

That’s the body Sulu spotted, and Kirk uses it to lure the Unity into the shuttle, and then tosses in some overloaded phasers and beams up just before the whole thing blows up.

Finally, the end is in sight. Spock’s puzzled by their hatred, the “possessed” crewmembers are all back to normal, and Hester-Jones decides to move on from Jim Kirk and transfers off the Enterprise.

Just understanding the plot in this one is difficult. It’s way too much crammed into too small a space to work in any way, shape or form. The art by Cockrum and Springer is, in a way, a minor miracle for not making the entire affair even worse. Visually, it’s not terrible. But it’s not good either.

And let’s look at the cover for this issue, which is confusing in so many ways. I’m going to assume the woman in the Starfleet uniform is supposed to be Karen Hester-Jones, though her outfit and hair are colored differently than inside the issue. If the man is supposed to be Kirk, it’s not at all clear, but who else would it be? I thought on first glance that these were Endeavor crewmembers, but that’s obviously wrong. And the story has six alien ghosts, and this cover features nine heads. I do like the overall composition, with the swooping Tholian-style lines, but that also has nothing to do with the story inside.

Last thing: the letters column is still being written by Mike W. Barr, who didn’t write this issue and won’t write another one until issue #17.

Clearly, this is a title in disarray. Marvel had more success with Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica, in part because those books found sympatico creative leaders in, respectively, Archie Goodwin and Walter Simonson. And while affection among the Marvel staff for Star Trek was clearly high, that direction was lacking in the comics themselves.

At least the next issue has a Frank Miller cover to look forward to.