It was 1985 when I returned to comics reading and collecting. I still dug the comics letters pages.

The letters in Marvel’s Star Wars series — the book that got me into the hobby — were solid. I remember seeing in issue #103 that the next issue was coming in 60 days, instead of the usual 30. I thought it was a typo. The two month wait revealed the book’s schedule had been demoted to bimonthly. Not long after that, the series was canceled.

Star Wars #103

(Jan. 1986)

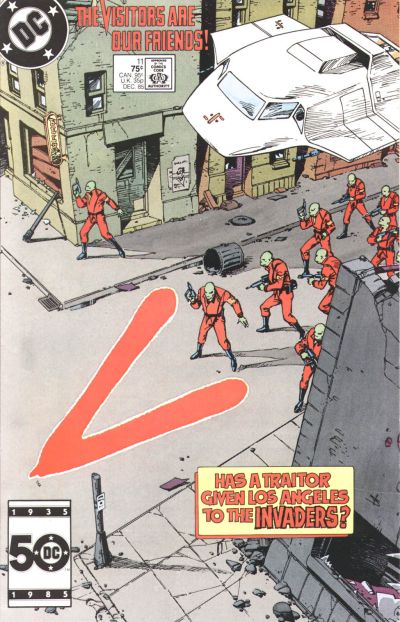

V #11 (Dec. 1985)

V #14 (March 1986)

Both V covers are by Jerry Bingham.

I also read V, which DC published based on the TV miniseries and then regular series. The original miniseries was terrific, and the followup, V: The Final Battle, was five-sixths great — the ending left a lot to be desired. The weekly TV series was a disaster and put out of its misery after one season. But I really wanted the show to succeed and stuck with it. There was nothing else sci-fi related on TV. If you liked that stuff, V was it.

The comic book version ran 18 issues — long past the series’ cancellation. And it had its high points: The covers by Jerry Bingham were terrific. Carmine Infantino penciled the series and his art had many of the same qualities I had come to like from his Star Wars run. And the letters pages also were lively, with lots of fans writing in and good engagement from the editor, Bob Greenberger. More on him later.

I wrote one fannish letter to X-Men editor Ann Nocenti and writer Chris Claremont in autumn 1986, after we had moved to Arizona. I was trying to work out the continuity of the Mutant Massacre storyline, and where X-Men Annual #10 occurred in the run. I’m still not clear on that point, but I’m also glad they didn’t publish it.

A year later, I was a student at the University of Arizona. My initial major was general business, mostly because I had to pick something and had no idea what else to choose.

In Canada, I had been a strong science and math student. But my interest in those subjects was frustrated by the way they were taught at the Arizona high school where I finished my diploma, and in my freshman year at university.

I had intended to take calculus in high school in Alberta, but Arizona — to no one’s surprise — lacked that option. In university, it was taught in an auditorium with 600 freshmen. The weekly session with a teaching assistant was not helpful. Teaching my group was a thick accented man unskilled at — and apparently uninterested in — helping us make sense of the topic.

Buying a set of notes for the class from a local copy shop, I basically re-took the class at home in the last weeks before the final. I got an A, but none of it stuck, and I was already looking at other interests.

I enjoyed being a university student, and liked taking classes on topics as diverse as psychology, world literature, and military history. Few of the other students in my classes, however, seemed to have any real interest in learning about these things. They loved the social scene, but classes were merely tolerated. They were something to get through on the way to the degree and job that would afford them the flashy car they wanted. It was disheartening to see so many people just going through the motions and failing to take an interest of any kind in the amazing world we live in and the opportunity we had as students to learn so much about it.

I also had always liked current affairs, history, and politics. In school, we had studied the history and culture of Canada, obviously, but also places like Africa, India and China. We also studied the industrial revolution, the Reformation, the Renaissance, and the Russian Revolution. Given the threat of global thermonuclear war, the latter fascinated me as much as it scared me. For more than a year after watching “The Day After,” I had to distract my mind with the radio to fall asleep each night.

At university, I took advantage of being a student to read lots of newspapers, magazines and books I had never had access to before. I often stayed up late to watch Nightline, with Ted Koppel. That was a great show, though I always wished he had more time to discuss things — an hour instead of a half.

All this inspired me to put more effort into my writing at college and the results were immediate — good grades and some very flattering compliments from teachers. That had never happened before. I also was really enjoying it, following topics down a rabbit hole and using the power of revision to refine ideas. It was at minimum very satisfying, and more often than not a lot of fun.

I also was reading as many comics as I could get my hands on. I was particularly fond of the X-Men titles and the writing of Chris Claremont. He had a strong style, but he also told complicated stories and defined his characters in ways other comics and books did not. I was a fan. It made me think that one day I could do something related to comics. Maybe.

I would read the Writer’s Market — a guide to publications that buy freelance work — in the university bookstore. It reported at the time that top talent at Marvel earned six-figure incomes. That seemed unreal to me.

But a career related to comics just didn’t seem like a viable goal. And certainly not a serious one you could confess in Tucson, Arizona, in 1987.

All of this came together in the pages of Avengers #289, which came out in November 1987. The book’s editor, Mark Gruenwald, had a series of columns he wrote, called Mark’s Remarks, that ran in the titles he edited. And in this one, he was talking about what it takes to be an editor at a company like Marvel. He wrote that comics require highly structured writing, like journalism. So knowing something about journalism was helpful. Read the whole thing here, especially section 3:

That stuck with me. It definitely played a role in my decision to switch my major to journalism. It wasn’t the biggest or most important reason. I had noticed in reading so many publications of all types that the people who worked on them seemed to really enjoy what they did, and that they felt it was important and worthy work. And that seemed like the right reason to point myself in that direction.

That choice was the right one for me. And I’ll never forget that moment of clarity, of the fuse that led to that decision being lit by reading that column.

I never had a chance to meet Mark Gruenwald, who died unexpectedly at the age of 43, in 1996. But I owe him at least a thanks for some simple words of encouragement. It’s amazing what a little of that can do — most people hear so little of it.

Next: Writing letters that actually got printed!