It’s taken me a awhile to get to reading the giant stack of comics that piled up the past few months. Reading them has been sadly dull — I don’t know if it’s the comics or if it’s me, though I suspect if everything was a great read I wouldn’t have written what I just wrote. So let’s get to it.

Dark Avengers/Uncanny X-Men: Exodus #1 (Marvel, $3.99) is the conclusion to the Utopia crossover storyline, and it’s reasonably good. That’s to be expected when you have folks like Matt Fraction writing and Mike Deodato and Terry Dodson drawing. The Utopia storyline was pretty overtly political for X-Men, starting with an initiative called Proposition X that would require medical birth control for all mutants. That leads to the mutants, who’ve established San Francisco as their new home base, going on the riot path and H.A.M.M.E.R. director Norman Osborn bringing in his Dark Avengers to restore order and discredit the X-Men and install his own lackeys — the Dark X-Men — as the public face of mutant kind. It’s a heavy handed and painfully obvious attempt to tie the mutants into the gay rights issues that are at the forefront of society. And that would probably work, but there’s such a sense of change fatigue when it comes to the X-Men franchise that none of this really has a chance to stick. It was only a year ago that the X-Men came to San Francisco, and nothing about that switch really stood out as meaningful or interesting — and now we’re on the move again to the remnants of Asteroid X, now renamed Utopia. It would have been nice for the X-Men to have stuck around San Francisco long enough for that setting to made a difference. And it’s hard when your arcs all run four, five, six issues to establish a real sense of place the way comics used to back in the days when they were periodicals through and through. I think of the first Wolverine series from 1982, where that setting of Japan really came to life and was important to the story. Nowadays, even with a half dozen spinoff titles, the X-titles (and Marvel titles in general) have become kind of cookie cuttered in the Bendis mode — where characters’ dialog rarely has much to do with the story and the overall tone is self-conscious and self-referential to the point of inanity. All of this was fresh 10 years ago, but at least for me, this style has worn out its welcome.

I also read the Utopia tie-in issues Dark X-Men: The Confession #1 (Marvel, $3.99), X-Men: Legacy #227 (Marvel, $2.99), both of which suffer from much the same symptom. Confession is basically an entire issue of Cyclops and Emma Frost having it out over the status of their relationship and their respective guilt and responsibilities in the whole thing. And character is important — it’s part of what made Marvel great — but this exemplifies the self indulgence that I think is plaguing the X-books in particular. Another example is The Uncanny X-Men #515 (Marvel, $2.99), the first issue of the new “Nation X” storyline that heralds the return of Magneto, usually a big event with lots of drama even when it’s not done well. But here, it’s sudden and just seemingly random. Even the things that should work don’t — a minor character dies in a rather nice scene, but again it’s a character who hasn’t been around long enough or done anything interesting enough for the reader to care about his passing with the same passion some of the X-Men display.

In the Wolverine corner of Marvel, Mark Millar and Steve McNiven’s alternate future run concludes in Giant-Size Wolverine: Old Man Logan #1 (Marvel, $4.99). Alternate future storylines can be fun, and this one has had its moments of coolness. But the ending, delayed from the regular run of the title to this special, is disappointing for just being so damn obvious. This post-apocalyptic Western tale, in which Old Man Logan has to rediscover his spine as he tries to protect his family from the victorious supervillains that rule the land. The end, however, sees Logan finally pop the claws and go to town on everyone — but it does so in so mundane and excessively violent a fashion that it’s hardly satisfying or even terribly interested. The art’s nice, even though it’s a bit gross at times, but this ending throws no curves at all and I couldn’t help but think, “That’s it?”

Still, it’s better than X-Men Origins: Wolverine #1 (Marvel, $3.99), the most recent Origins one-shot. I guess this does a decent job of recapping the character’s origin and making it jibe, both storywise and visually, with what appears in the movie of the same name. But in simplifying the story, it loses the interesting parts of the good stuff and exposes the lame stuff for being truly lame. It also doesn’t do much to explain itself — like who are Heather and James Hudson, who weren’t in the movie? The art, however, is nice — no surprise since it’s by Mark Texeira, who did a good job drawing the Wolverine series way back in the early 1990s.

X-Factor #47-48 (Marvel, $2.99 each), continues to be a consistently entertaining read. Yeah, it’s gotten complicated, with future Dr. Dooms, an adult Layla Miller, a future Cyclops and more Madrox dupes than you can shake a stick at. But writer Peter David does a good job of giving everyone a personality and structuring his story so that it’s entertaining even if you don’t remember every detail of the previous 46 issues.

Before we leave the mutant corner of the Marvel Universe, there’s X-Men Forever #7 (Marvel, $3.99), which reminds me how great writer Chris Claremont was at establishing a new direction for a series and how quickly the new status quo could be forgotten. After a memorable five-issue opening arc, the last two issues have been a lot more murky and directionless. This one features a lot of flashing back on Nick Fury’s part to the days when Logan (currently believed dead in this timeline) did a lot of dirty work as a solider. It’s all still very recognizably Claremontian, which is comforting at times, but lacks the obvious forward momentum and focus of the first arc. Given that the outcome of Claremont’s stories usually depends greatly on the talents of the artist he’s working with, Tom Grummett can’t return to these pages soon enough.

Fantastic Four #569 (Marvel, $3.99) wraps up another Mark Millar run, though this time without the artist who kicked it off, Bryan Hitch, and with an assist on the scripting from Joe Ahearne. This is a definite ending point, though I recommend rereading as much of the run before trying to tackle the finale as possible because who’s who and what’s what is, once again, a complicated matter. The best part of the book comes at the end, when Ben Grimm’s wedding day arrives at long last. Removed from the plot complexities of the first half of this book, the characters are fully enjoyable and the situation surprising for the nature of the conflicts and how they play out. The art, by Stuart Immonen, is a good imitation of Hitch’s style, giving a bit more warmth to the characters. Looking back, the run didn’t measure up to the potential of the earliest issues. Seeing the acclaim for the follow up run by writer Jonathan Hickman tells you all you need to know about fan reaction to Millar’s run. But it still turned out well and I think will grow a bit in fans’ eyes over time.

Lastly from Marvel is The Amazing Spider-Man #602-604 (Marvel, $2.99 each). The plot in these issues, written by Fred Van Lente, features a good twist on the old Chameleon character (he’s been a villain since way back in ASM #1) as he mistakenly takes on the appearance of Peter Parker without knowing he’s Spider-Man. There’s some funny moments as Chameleon manages to fix a lot of Peter’s personal problems without really trying too hard. The return of Mary Jane figures fairly prominently, not completely justifying three consecutive MJ-themed covers, but OK, they’re well done. The Amazing Spider-Man has succeeded in its attempt to be a serial of its own — it may be the only part of the Marvel Universe that doesn’t rely on constant crossovers or participation in things like Dark Reign. Shipping three times a month, it’s also worked out a unique rhythm to its plotlines that is most like that of a TV series. I don’t know how much of an effect this had had on readership — whenever I ask at the comic shop, I’m told that overall interest in Spider-Man is down — but I think Marvel should stick with it because it’s, at the very least, different.

Having dug through the Marvels, it’s time to look at a few DCs from the Batman corner. Batman and Robin #4 (DC Comics, $2.99) is the first issue drawn by Philip Tan instead of Frank Quitely. I think it takes Tan a bit to find his groove on this issue, as I had a hard time following the art in the early pages but was very much enjoying the issue by the end. Grant Morrison’s story brings back The Red Hood, though who’s under the hood remains a mystery at this point, and his sidekick Scarlet. This is a good Batman story — the plot, villains, conflicts and visuals all work as well, if not better than, the previous Quitely-drawn issues.

It’s only moving on to read Batman #689-690 (DC Comics, $2.99 each) that I wonder what specific purpose each book is intended to serve. Maybe it’s just that with Batwoman having taken over Detective Comics, they needed to start Batman and Robin to have that second main Bat-title. I don’t know. But these issues, written by Judd Winick and drawn by Mark Bagley, were also quite enjoyable. Bagley’s art, especially, is refreshing on Batman because his style is so associated in my mind, and I’m sure others’, with the sunnier superhero fare of Thunderbolts and Ultimate Spider-Man. His Batman has some of the same quality, but after so many years of downplaying the superhero aspect of Batman it comes off as cool and interesting. Of course, Winick’s script helps, emphasizing as it does new Batman Dick Grayson’s happier outlook on life when compared to that of Bruce Wayne.

Lastly, comes Detective Comics #855-857 (DC Comics, $3.99 each), featuring solo tales of the new Batwoman by writer Greg Rucka and amazing art from J.H. Williams III. Considering how easy it would be to butcher a series about Batwoman, who was introduced to the world in a flurry of news articles about her homosexuality, it’s a bit of a minor miracle that this is so good. A lot, I think, comes down to Williams, who remains underrated despite outstanding work on Alan Moore’s Promethea and the seemingly lost Desolation Jones with Warren Ellis. The “Alice in Wonderland” villain is beautifully rendered, the pages are shockingly designed to be read as comics rather than movie storyboards and the imagery is powerful and beautiful all at once. And it does so with an unmistakable homoerotic undercurrent that’s attractive and playful in a way no comic has been since Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbe’s Cobweb feature from the ABC Tomorrow Stories series. And let’s not forget Rucka, who gives Kate Kane everything a character needs to be interesting and true to herself without doing the obvious sex scene. Instead, there’s a rather romantic dance between Kate and Maggie Sawyer from the Superman books that is really well written, staged and drawn. I also like that this series doesn’t interact with the other Batman books, that the series is getting a chance to stand on its own and hopefully develop its own identity and audience. There’s also a backup strip in these issues, written by Rucka and starring The Question. This is the new Question, former Gotham City cop Renee Montoya, and it’s so far so good there too.

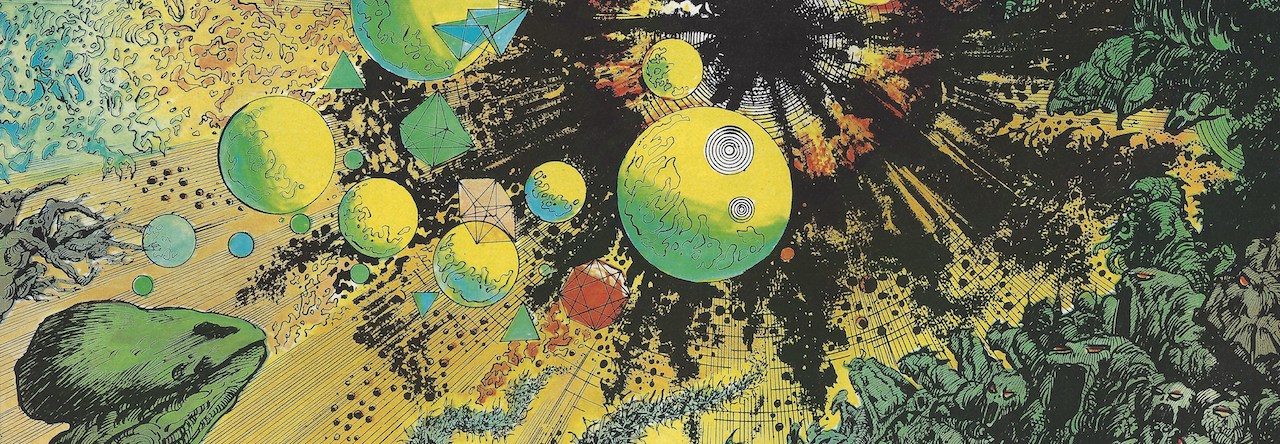

We’ll see how much more of the pile I can plow through this week, though I’ve been on a real Jack Kirby kick of late and am interested in revisiting some of his work. Also, I’ve been reading Moebius — Blueberry Vol. 1 (the Marvel/Epic version) and The Airtight Garage just arrived in the mail today — and picked up a couple of interesting items in France and Italy that I want to get to and will … eventually.

Like this:

Like Loading...

It’ll be interesting to watch, however it turns out.

It’ll be interesting to watch, however it turns out.